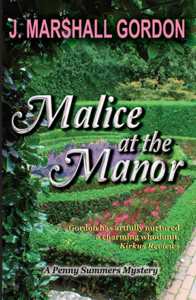

Malice at the Manor

By J. Marshall Gordon

Chapter One

Strolling through a well-planned garden always brightens my day. And I occasionally pick up an idea or two. As my Grandpa Jack used to say, Penelope, if you don’t learn something every day you’re not paying attention.

A year ago I’d become a Master Gardener and when I realized that I enjoyed just about every aspect of gardening, I enrolled in the spring semester of Madison Lerrimore’s Residential Design course at Annapolis Community College. A week after the last class, we’d come to North Carolina to visit one of the most interesting landscapes we’d studied.

Madison and I were rambling through hemlocks, sparkling hollies, and groves of flowering fruit trees and colorful shrubs at Brantleigh Manor, the finest example of Italian Renaissance garden design in America. Overhead, an iconic Carolina blue sky reigned supreme. Not a cloud in sight.

Our guide was the landscape architect who had laid out the gardens in 1905. Actually, he wasn’t the designer, Frederick Law Olmsted, but his twenty-first century doppelgänger.

“Here in the Glen—” he harrumphed to ensure our attention “—I transitioned to a more naturalistic style—like my first design … ”

I acknowledged his smug smile. Every student of garden design knows the story of Olmsted and Vaux winning the design competition for New York’s Central Park in the 1850s.

Between his observations, we followed a winding path through patchworks of flowering trees and shrubs punctuated with sweeps of crayon-bright tulips and sun-dappled daffodils. With photo opportunities beckoning at every bend, I couldn’t resist taking shots that I would assemble into a PowerPoint that Madison could use in next spring’s intro course. I included Madison in one shot, her short dark hair and lack of make-up contrasting with the luscious pink blooms of the flowering almonds where our Olmsted had once again halted us.

“I designed this entire Glen,” he said with a hint of exasperation as he swept his walking stick in a complete circle, “as an arboretum of evergreens … a winter garden if you will. We planted every kind of fir, pine, spruce, and hemlock and several kinds of hollies.”

His ruddy cheeks, balding forehead, long gray whiskers, greatcoat and walking stick made him a dead ringer for his portrait on the estate’s brochure.

“So much of Brantleigh Manor’s landscape has been changed over the years,” he continued. “Regrettably, here in the Glen, in my opinion, the alterations have not been improvements.”

As his tone shifted into resentment, my ears perked up.

“After Governor Brantley’s death,” he said, “wouldn’t you know, his widow decided she’d prefer a more colorful plant palette. She had the majority of my evergreens yanked out and replaced with what you see today.” He stomped his cane, narrowly missing a buckled shoe. “Without so much as a by your leave!”

It was ingenious, I thought, for Brantleigh to employ docents in the guise of America’s first landscape architect. For visitors who might imagine that gardens materialize spontaneously, their presence underscored the reality that all gardens are really collaborations with nature that were birthed in a designer’s imagination.

“Really,” he said. “How tedious!” His eyebrows furrowed. “By then my Glen was nearly forty years of age … and growing apace.” He huffed impatiently. “She should have asked my opinion.”

While my eyes, I’m sure, rolled at his blatant theatricality, it was also true that if Madison weren’t wearing her jean jacket embroidered with Grateful Dead bears, I could have easily imagined we were with America’s first landscape architect, the genuine Frederick Law Olmsted, more than a hundred years before.

“By then, unfortunately,” he said, his face relaxing, “I was in my gra—”

“Mo-om! There’s a man down there!”

The kid’s scream ratcheted up my pulse in an instant. Until that moment, I hadn’t noticed either the boy or his mother a hundred feet or so ahead of us. The mom looked up from her phone and glanced at him, thinking perhaps it was a stunt to get her attention.

“Okay, young man,” she said, “that’s enough.”

As they hustled past us she grumbled, “This kid and his overactive imagination … ”

“But Mo-om … ”

Do not ever discount the testimony of a child, whispered my late lamented Grandpa Jack who occasionally offers observations from beyond the grave.

I dashed to where they had been. Madison and Olmsted hurried to catch up. Nothing appeared amiss.

Tarry! Grandpa Jack whispered. The boy said the man was down there.

Down there? Where? Then I realized that the mountain laurel on both sides of the path obscured a minuscule creek that crossed under it. I snagged a branch laden with pink posies and pushed it aside. Then another. And a third. OhMyGod—

“The kid was right,” I said, my breath catching as my adrenalin bubbled, “it’s another Olmsted.”

“Penelope,” Madison croaked, “you’re kidding … right?”

“Unfortunately—” I said, but couldn’t say more.

Our docent’s double was down there, literally under our noses, in the tiny rivulet.

Déjà vu all over again, whispered Grandpa Jack, who’d always enjoyed quoting Yogi Berra.

Olmsted’s eyebrows arched into the shape of violin f-holes as he pulled a phone from his greatcoat and gave up channeling America’s first landscape architect.

“Mike. Ned here.”

Ned? I’d assumed he was Wayland somebody, Madison’s stepfather, who she’d told me would be our guide. She hadn’t seen him since high school and a key reason for planning the trip was her eagerness to reconcile with him.

“We’ve got a problem,” Ned said to his phone. “We’ve found Wayland. He’s either drunk or sick or—”

Dead’s what I think, whispered Grandpa Jack.

Madison screamed and quickly looked away.

When we’d met our guide this morning, Madison had hesitated slightly but said nothing. I never guessed that he wasn’t her stepfather.

“Just shut up a second,” Ned screamed at the phone. “We’re in the Glen. And FYI — the kid who found him and his freaked-out mom are on their way back to the Manor.”

Ned tapped off his phone and scanned the path. The boy and his mom were long gone. Two elderly women were admiring an enormous Yoshino cherry in full pink regalia a couple of hundred feet behind us. One carried a cane and the other used a walker. Beyond us, an elderly gray-haired guy dressed in black was either unconcerned or unaware of our predicament. He turned his back and with a slight limp continued toward the Waterfall Garden.

“Let’s get him up,” Ned said.

Madison’s hand jumped to her mouth.

I scrabbled down to the little creek and felt the man’s wrist for a pulse. I’m no expert but I couldn’t detect one. Grandpa Jack, who championed the Great Books program at St. John’s College, used to tease me about wasting my time reading mysteries. I’d told him I occasionally come across a tidbit I file away and trust that I’ll never need in real life. Which is why I quickly checked Wayland for signs of violence. His clothes appeared free of blood and I could see no holes of the bullet variety or otherwise.

“Ned,” I called up, “give me a hand?”

Madison, wide-eyed, stepped back further.

With an arm around his chest, I heaved him like a store-window manikin until Ned, on his knees, could get a grip on his waistcoat. Already stiffening, the poor guy was the literal definition of dead weight. By the time we tugged him up onto the path and turned him over, I was out of breath.

“Holy—” Madison stammered, gasped for air, threw her hand to her face and began to wail.

I knew the horror of finding a family member dead, familiar with the anguish that never completely fades. But, right here and now, what? Call 9–1-1? The F.B.I.? The State Police? Flummoxed, I stared at the dead man. I was like an uncertain zombie. One moment a student of landscape architecture, and the next, an unwilling participant in a grisly scenario. Tomorrow’s local headline formed in my mind’s eye: EX-NAVY PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICER FALTERS IN CRISIS. The day had turned upside down, left me in panic mode, a captive in a terrifying new reality.

Madison’s stepfather wasn’t as tall or as gaunt as Ned, but was outfitted identically. Mud streaked his greatcoat, his waistcoat was unbuttoned, his shoes scuffed. A mountain laurel twig served as a hook for the straw boater he’d lost when he fell. His wig was gone, leaving a crop of thinning buzz-cut hair that made him look like a long-retired Marine. Worst of all was his mouth stretched awkwardly, his face a spasm. I lifted an eyelid. A foggy eye stared skyward.

“He’s beyond help,” I pronounced.

“My s … step … father,” Madison stammered. Her tearful face crumpled into an equally crumpled blue bandana.

My heart went out to my mentor. She and I had become friends almost as soon as her design course began. The weekend before we came to North Carolina she and her partner and their daughter Kalea had helped celebrate my thirty-third birthday at O’Leary’s, a few blocks from my Eastport condo.

Ned took charge, gesturing toward a grove of native rhododendrons a couple of yards uphill from the path. “We have to get him out of sight.” Madison’s wailing intensified.

“You’re not supposed to move a body,” I said.

You’ve read too many murder mysteries, Grandpa Jack whispered.

“He’s already been moved,” Ned countered.

The dead man’s shoes plowed little furrows in the mulch as Ned and I schlepped him toward the rhododendrons. In spite of the pleasant morning, by then I was perspiring profusely, far more than what my Great-Aunt Zelma would call glistening. Madison walked alongside us to block the view from the two women who were closing on us, having finished marveling at the big Yoshino cherry. When we laid him down, she stumbled a few yards further up the hillside and upchucked.

Ned clicked his phone. “Michael, update. Wayland’s dead.”

Grandpa Jack had been right. Again.

When I was growing up in Annapolis, my Grandpa Jack was the dean of St. John’s College, and expected me to apply there after high school. Instead I opted for the Naval Academy. In so many ways, especially after mom deserted us, he was like a doting parent and when he died, I was half a world away, a public affairs officer on the USS Enterprise during the Iraq war. In the privacy of my stateroom, I wept, devastated, unable to attend his funeral.

But his death didn’t end his caring for me. I still hear his occasional whispers. At first it was unnerving, but these days I’m grateful for his suggestions although sometimes he comes across as a know-it-all.